In 2001, I and one of my great friends Nalin, were working on a secret project. We decided to call it "Project Libra". The Project involved exploring ideas for unlocking value from a company which I thought was highly undervalued.

While preparing for a lecture today, I came across the transcript of a chat I had with Nalin on Project Libra. This chat took place on 19 May, 2001. I reproduce here the transcript of that chat. I decided not to edit anything out or make any corrections whatsoever.

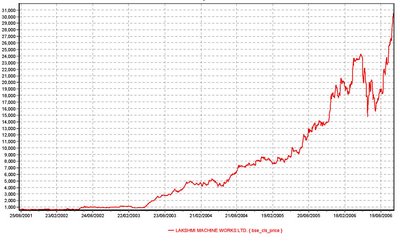

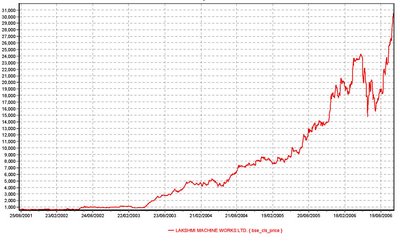

At the end of the transcript, I have placed a stock price chart of the company from around the time of that chat till recently. It became a 35-bagger. The company's name is Lakshmi Machine Works.

Chat

Date: May 19 2001 - 11:58am

Sanjay says:

Hi Nalin, will try to send Libra comments thru MSN

Nalin says:

Okay - send

Waiting for Nalin to accept the file "Libra Comments.htm" (4 Kb, less than 1 minute with a 28.8 modem). Please wait for a response or Cancel (Alt+Q) the file transfer.

Transfer of file "Libra Comments.htm" has been accepted by Nalin. Starting transfer...

Transfer of "Libra Comments.htm" is complete.

Nalin says:

Okay got it. Tell me when you send the Libra stuff. Bye

Sanjay says:

Wait

Nalin says:

waiting

Sanjay says:

is the file legible. it may not be i am sending a text version

Nalin says:

okay send

Waiting for Nalin to accept the file "Libra comments.txt" (4 Kb, less than 1 minute with a 28.8 modem). Please wait for a response or Cancel (Alt+Q) the file transfer.

Transfer of file "Libra comments.txt" has been accepted by Nalin. Starting transfer...

Transfer of "Libra comments.txt" is complete.

Sanjay says:

will SMS u when ready with Taurus comments

Nalin says:

Got it thanx. Actually I don't remember myself if Rieter was under hostile takeover. Remember I told you in Delhi about a Swiss activist investor. Do you remember which company he was trying to acquire - why is Rieter or some other ?

Sanjay says:

That guy sold stake a pharma co to another pharma co

Nalin says:

Okay - anyway I had already deleted the hostile takeover reference.

Sanjay says:

OK spend a couple of minuts reading my note. I'm waiting

Nalin says:

Okay

Nalin says:

I'm still reading it - but I have one question - maybe you can answer while I continue reading - why should normal dep be 50% of dep charged ?

Nalin says:

Also, on the financial engineering thing - if you took out Rs 100 Crore from the company (by replacing it with debt) it won't earn 45 Cr of discretionary profit a year.

Nalin says:

I agree, in general, that financial engineering can add value. But only when cash earnings. (They may already be stable - but we're not sure of that yet). Also, financial engineering in India is a very difficult task - and an acquirer would not want to pay now for benefits of financial engineering which he'll do post acquisition.

Sanjay says:

Take a look at the gross block and the accumulated depreciation. Gross block is 603 cr and acc dep is 407 cr. They are definitely overproviding depreciation. The amount of money that would be required to replace this gross block is definitely a lot more than the net block figure of 196 cr

Nalin says:

Sorry I missed a work in that message. I meant to say "But only when cash earnings are stable"

Nalin says:

If you feel that they are overproviding dep, then that is an additional upside which we will find out in detailed due diligence (if we are ever allowed to do that ) - at this stage its just a guess - we can't expect someone to pay top dollar for a guess.

Nalin says:

For all we know their assets might need a major revamp - which they have been delaying. Also in cash earnings we must deduct their increasing need for working capital

Sanjay says:

I am quite confident of the overprovision. Take a look at all the cash they have squandered away thru stupid diversification over all these years. THow did they finance it? not from new issue of shares, but from debt and internal accruals. Basically they had too much cash and insteadd of returning it to stockholders they simply threw it away

Nalin says:

You are right they might have overprovided depreciation. Do you want to base our presentation on that premise. Are you sure enough to make it a KEY assumption ?

Nalin says:

I'd rather just make it an additional upside

Sanjay says:

Not at all. What I want is to inform our investor group that this is classic case of massive misallocation of cash generated from operations. And that a rational person in control will have an opportunity to correct that misallocation and create value

Sanjay says:

Fine, you'can make it an additional upside but I should be in the document

Nalin says:

Okay - so we make that an upside that an acquirer gets - when he gains control. But I don't think we should ask him to pay for an upside - that we have no way of proving at this stage.

Nalin says:

Then the strategy remains more or less unchanged ?

Sanjay says:

Please also notice that my additional debt of Rs 100 cr requires an annual interest outgo of only Rs 15 cr and I have assumed c discretionary cash earnings of 45 cr p.a. at least until TUF benefits are available for the next three years. Even if the discretionary earnigns come to less than 45 cr, I can still pay a Rs 100 cr dividend financed out of from borrowed funds because the company is hugely

Sanjay says:

underleveraged.

Sanjay says:

Therefor I can bring my effecive cost of acqusition to Rs 18 cr for a 40% stake

Nalin says:

Like I said earlier - financial engineering is not something an acquirer will pay for up front

Sanjay says:

Why not? I would if I was certain of the benefits. If we get more info on the company's cash generating abilites then I would very gladly pay for financial engerring value

Nalin says:

In some cases it makes sense to go to the hilt in paying. In this case it makes sense to pay as little as possible - and not factor in too many upsides

Nalin says:

How do you get certain of the benefits ?

Sanjay says:

I agree with the conservatinve approach u are taking but putting a value equal to 100% of adjusted book value is too conservative, I feel.

Sanjay says:

We go to Coimbatore on a fact finding mission. we can control costs by travelling by train

Nalin says:

Its conservative - but in this case, paying more doesn't achieve much additional advantage - it disproportionately increases our downside risk. If we stick to market price in our bids - we have almost zero risk of loss - and a considerable upside.

Nalin says:

Even getting control of this company is very difficult - with labour, politics etc involved. Also, it probably has liabilities we haven't even dreamed off - such as corp guarantees for the steel project. Its a mess we don't want.

Sanjay says:

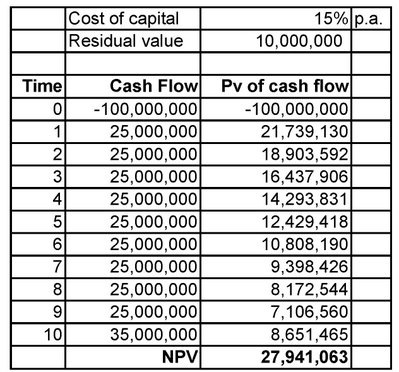

Ok think of it this way. Suppose, the amount of cash that can be taken out of this company without hurting it is only Rs 35 cr p.a. for the next three years and we are use a discolunt rate of 20% p.a. Then the present value of the next three year cash flows alone comes to Rs 650 per share.

Nalin says:

Its pure GM - with controlled downside risks

Sanjay says:

Nalin how can we do a successful GM when we are delaing with promoters who are not cash rich? I thought u did that cash rich promoters

Nalin says:

Listen - the way the industry is going - the company may need to get cash negative - to be able to emerge a strong player

Sanjay says:

But we'll be out well before that happens

Nalin says:

How do you get out ?

Sanjay says:

Leveraged recap can esnure that our cost is negligible. Then whatever we sell the company for is profit

Nalin says:

You can't do a leveraged re-cap if we fear uncertain cash flows - because of a recession + competition. Depending only on the TDF is not enough.

Sanjay says:

To quote u, "I agree to disagree!"

Nalin says:

But what strategy do we put in the book

Sanjay says:

I guess it would be best if we were to fix the meeting for wednesday and I come to mumbai on Monday and we spend 2 days on it

Sanjay says:

Im ust tell u that I am enjoying working with u

Nalin says:

Thats good.

Nalin says:

Lets give one last attempt at coming to consensus now.

Nalin says:

Tell me why is my strategy flawed. Let me defend it for a change.

Sanjay says:

It all comes down to valuation. You are being unlta conservative in valuing this company. A company that produces a cash profit of 70 cr cannot be worth less than the book value of 117 cr. This is true even if a large part of those earnings are not discretionary.

Nalin says:

I'm not saying its not worth more - I'm just saying we shouldn't pay more - what's wrong with sticking to a low price ?

Sanjay says:

Your views on valuation in the presentation are so pessimistic that the whole project will turn off investors

Sanjay says:

and I thought u were an investment banker!

Nalin says:

I WAS an investment banker. Now I think more like a value investor.

Nalin says:

My views on valuation were given on the next page - where I said that it could be worth Rs 1800

Nalin says:

Did you get the presentation ?

Sanjay says:

LOL! i agree we sohuld pay less if we can get away with it but how to achieve it is the issue here. We cannot do this deal unless we convince investors that this is a sitting duck

Nalin says:

But did you get the presentation - I hope you aren't refering only to my initial note

Sanjay says:

That 1800 is based on relative valuation with peers, something that may be difficut to sell to our investors.

Nalin says:

Before I proceed I need to know if you got the presentation

Sanjay says:

I got the presentation. Also, our strategy shoudl reflect the illiquidity of the stock for exit. We cannot sell a deal to investor on the basis that one of the exit routes will be thru the market when dailty volume is 15 shares. We cannot also tell them to hold it as a value stock. Our investors want to make a quick buck.

Nalin says:

I mentioned exit through the market only when the deal is on (and only to a very limited extent). I mentioned illiquidity when I said only 32,000 shares were traded last year.

Nalin says:

Holding on to the stock is a worst case scenario. I think we shouldn't proceed unless we have an investor who is willing to take that risk. Because its a real risk. I can think of no other approach which has a lower risk.

Sanjay says:

The stock is so illiquid that mkt operations after Public Annoucement will not be feasible. under such circumstances, why not have a conditional two-tiered tender offer which guarantees either control or exit thru tender in their counter offer?

Nalin says:

Let me think about this for a minute ?

Sanjay says:

Say a 7% toehold at 850, a 21% offer at 1500 subject to minumum level of acceptance of 20% with a lower offer price of 850 if shares tendered are less than 21%

Nalin says:

I think the problem again will be return on investment. We did this exercise in Taurus. The return on investment was just too low

Nalin says:

What should be the offer size ?

Sanjay says:

The toehold will cost only Rs 7 cr. A 21% offer will cost 38 cr., 50% of which or 19 cr will be cash escrow

Nalin says:

You are saying a 21% conditional offer, with 20% minimum acceptance ?

Sanjay says:

yes

Nalin says:

But in terms of risk - how is this different from what I said. You still run the risk of getting stuck with acceptances in your offer at Rs 850 ? But the downside is that return on investment goes for a toss. It was bad enough under my option at only 50% annualised.

Nalin says:

You also run the risk of actually getting 21% at Rs 1500

Nalin says:

Are you saying the only problem with my plan is that we won't get an investor willing to take the risk of a residuary holding at Rs 850 ?

Sanjay says:

I am unable to explain. Either we have to meet or I have prepare a note on bidding strategy explaining why I think that a conditional offer may make sense. The main reason is that a conditional offer is a hedge. But it imposes an ban on market purchases. But mkt purchases are not going to happen in any case in this stock/

Nalin says:

Okay - we'll discuss conditional offers later. Lets go back to why my plan is flawed ?

Sanjay says:

Look at pg 18. What if they don't buy us out? What if they go to instutions and get them to not tender to us because of lack of significant premium to market offer fro us. There are 100 shares. 13+21+33 (rieter,promoter,instutions) or 67 will not come. 20 shares are are missing. therefore 87 will not come. we already have say 7%. so we'll get only 6% if institutions do not tender.

Sanjay says:

they can simply ignore us and just get institutions to not tender.

Sanjay says:

so we end up with 13% at 850 and no control just apin in their necks

Sanjay says:

in order to get the institutions to tender we have to offer a significant premium to market otherwise they will have an excuse for not tendering. I saw this in Gesco case

Sanjay says:

If institutions do not tender and they don't make a counter offer we are fucked

Nalin says:

There is only a small chance that FIs will pre-agree not to tender. I think FIs will keep quiet about their intentions - therefore LIBRA will be forced to act. Also Rieter may want to ext. I don't think Libra will ignore us because they will not want to take any chances of losing control.

Nalin says:

But assuming this happens (its only a 2% chance) then our max downside is we are stuck with a 15% stake at 850. In other options there are worse risks.

Sanjay says:

In case of Gesco, the institutions made it very clear that they will not tender unless they got book value. In Gesco the book value was 54 and return on equity was less than 5%. So we told them that the stock is not worth book value because ROI is so poor. Thay told us to fuck off and come back with a 54 offer.

Sanjay says:

In LIBRA book value is 2000 even though a lot of it is water, but it does give a huge excuse to institutions to not tender. Also there is a history of this stock which at one tiem sold for Rs 10,000

Nalin says:

FIs will certainly want to put pressure on LIbra to give a better counter offer. They won't want to give them guaranteed comfort - and suggest they don't need to counter offer. Rieter will also want a higher counter offer - so there won't be any guarantees from that end eithre

Nalin says:

Anyway - we are talking about the same flaw - the chance (in my opinion small) of a residuary stake at Rs 850 ? Is there any other flaw ?

Sanjay says:

Precisely the point. In order to put this company in play we have to make institutions the sellers. Once we do that with our offer then our offer is the minimum they would get and they would demand higher from promoters or Rieter.

Sanjay says:

Unless we induce instutions to sell, we cannot succeed. becasue in any proxy contrest tyhey would side with management

Nalin says:

Okay - but we have to be careful not to introduce higher risks just to eliminate that risk - also be careful not to dilute returns too much. If you can come up with such a plan good. If we can't - we scrap this project.

Sanjay says:

My basic difference with you on this is that u are approaching it as a GM operation, whereas I am appraoching it as an acqusition prior to a leveraged recap, but which could also become a GM operation.

Sanjay says:

Hopefully it will be the later

Nalin says:

I strongly feel that we should not acquire this company - but stick to GM

Sanjay says:

But even if it turns out to be the former, I can do a recap to get my cost to negligible levels

Nalin says:

Do you want to discuss GM vs acquisition a little more ?

Sanjay says:

OK

Sanjay says:

Let's talk about promoters. GM is done with cash rich guys not poor ones

Sanjay says:

thesze guys are leveraging to creep up. OK, chola may be a white knight in which case our probability of GM is that much higher

Nalin says:

Overgeneralisations are dangerous. Every situation is different. In this case, we keep the cash required to buy us out low - so that they can actually buy us out - therefore a low bid

Sanjay says:

u do have a point there

Nalin says:

If Cholamandalam is appears as a white knight and gives a counter offer without buying us out - we lose - but hopefully without a loss.

Nalin says:

Also please note if we start a bidding match, Cholamandalam can still come in - in that case our losses would be even higher

Sanjay says:

now u're making sense

Sanjay says:

what 2 do?

Sanjay says:

OK, here;s a plan, we go with your presentation with John and ASit and see how they feel about it. Do u want to talk to Asit about Libra?

Sanjay says:

On pg 19 of your presentation u mention, "If promoters do not give counter offer - we become largest shareholder". I don't agree with this because we will not have significant tenders at a low price offer if institutions are not participating

Nalin says:

Listen I don't want to steamroll you into this. So you keep thinking. I'll keep working on the presentation. Overall, I think we should give both plans to Asit and John, just to show that we have more ideas where Taurus came from. On whether the plan is good or not - we can decide tomorrow

Nalin says:

Okay - I'll take care of that

Sanjay says:

Just think about this aspct

Nalin says:

Yes - this requires a lot of thinking - I agree

Nalin says:

Earlier when I said we should give both plans to Asit _ I meant both projects not both plans

Nalin says:

Someone has just sent me an email from gescocorp. Should I check and see ?

Sanjay says:

WHATTT????

Nalin says:

Wait I'm checking

Nalin says:

A friend of mine has just joined Gesco Corp. He's coming to visit tomorrow. How wierd.

Sanjay says:

Don't tell him about me!

Nalin says:

I have this feeling that destiny is just a game played for God's perverse amusement

Nalin says:

I won't.

Sanjay says:

I wanna live

Nalin says:

Okay.

Sanjay says:

ask him what's happening in the company

Nalin says:

Any more detailed comments on Libra - such as page 19 ?

Nalin says:

I'll work on another draft of the presentation and send it to you - in the meantime you think strategy. But hurry up with Taurus. Because I need to print the presentation today

Sanjay says:

OK Give me 2 hours on Taurus. I agree with most of your work there, just a few points I want to add/amend

Nalin says:

Okay talk to you later then ?

Sanjay says:

In libra disagreement is on valuation, and accoringly on strategy, but i see your point that a alow priced offer will enable the promoters to buy us out at a lower cost

Sanjay says:

Bye?

Nalin says:

It was a stimulating discussion anyway. Bye.

Sanjay says:

bye

SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENTS: